4 Reasons why you should stop doing portfolio projects

When I’m talking with students and artists who want to get into storyboarding, they are almost always working on a 'portfolio project'. A big and exciting sequence that they believe will help them break into the industry. This seems to make sense, after all a portfolio with amazing sequences is what will get you a job, right? . . . Right?

Well, I actually believe there might be more efficient ways to grow your skills and make the connections that will help you get that first job. As usual when I’m giving advice, this is something that I actually used to do. So I’m not judging anybody, I’m only trying to help you avoid the pitfalls I stepped in myself.

Before we start, I think it is important to take a moment and think about what a portfolio is and what it needs to do: I would say that a portfolio is a selection of your strongest work. It should showcase your skills, but also your interests. Apart from giving the reviewer an impression of your technical strengths it should also show them who you are and what kind of stories you like to tell.

And to make a killer portfolio I think working on epic portfolio sequences might actually turn out to be counterproductive. So here are four reasons why you should stop doing them!

1. You’re putting too much pressure on yourself

Did you ever get a really nice, expensive sketchbook? Hardback-binding, beautiful paper, bought in a proper art store . . . But when you tried to sketch in it, it just didn’t work. And then when you’re working on scrap paper, or that cheap sketchbook you got from the stationary store around the corner, your sketches are so much better? Your portfolio project is like that beautiful, leather-bound, expensive sketchbook. It seems to be everything you want, but it just doesn’t come to life.

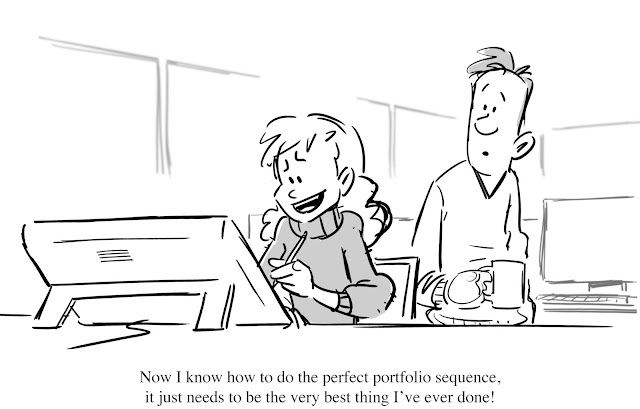

By labeling the sequence you’re working on a portfolio project from the start, you are putting way too much pressure on yourself and your project. Basically what you are saying is, this sequence has to be one of the very best things I’ve ever done. And striving for perfection is the best way to louse up any project.

Maybe, instead of starting a sequence destined to be in your portfolio, just do a rough sequence. Don’t spend too much time thinking about it it, just get going. Draw fast and loose. When it’s done show it to some people whose feedback you value. Listen to their notes. If you feel like it do a second pass, if you’ve lost your motivation for this story scrap it and do another. Do it quick, have fun, don’t overthink it. Because:

2. Fast and simple is better than elaborate and epic

Artists working on a ‘portfolio sequence’ tend to make their sequence a big and epic project. They spend a lot of time on the lore, the world, and the characters. . . But you’re not making a pitch bible, you’re trying to showcase your storyboarding skills.

In many cases the idea behind your sequence is less important than the way you execute it. Really, when you break it down all you need is a character who wants something that is hard to get. That’s it. It should be clear what the character’s motivation is, why they want this specific thing, and their should be one or more clear obstacles in their way.

It can be a romantic story about a teenager trying to dance with his crush at prom but there’s a big jock in his way, or it could be a funny story about a mouse trying to steal the cheese out of a mousetrap without waking up a sleeping cat, it could even be a big action sequence where a thief tries to escape from the police with the loot from a bank-job. But don’t get too hung up on these specific types of stories. The genre of your sequence might be less important than you think . . .

3. There is no such thing as the perfect portfolio

If you watch presentations by recruiters, or story artists from big studios, something you hear a lot is that your portfolio should have these three or four specific sequences: one comedic, one dramatic, an action sequence, and some people also like to see a personal story. This makes sense, it shows you have the range to handle different types of stories. That you know how to handle a specific tone. It also shows where your strengths lie as a storyteller. And it gives an impression of who you are both as a person and as an artist.

The problem is that most aspiring storyboard artists take this advice for gospel. So people are talking about their “dramatic sequence” or their “action scene”, like they are checking off the boxes for a perfect formatted portfolio. But, that perfect portfolio doesn’t exist!

Imagine that you are a recruiter looking for a storyboard artist. And someone has sent in a portfolio with only one sequence in it, but that sequence happens to be an Indiana Jones-level action scene. It’s thrilling, exciting but also funny with great characters. Also the rest of this artist’s portfolio shows a strong sense for composition and drama. It has a cool comic, some funny gag drawings and a some observational drawings that show an ability to draw quickly and clearly. Now imagine there’s a second portfolio, the work is on a more mediocre level but the portfolio ticks all the boxes: the obligatory three or four sequences, gesture drawings, and a page of animal sketches. Who would you hire?

Does this mean that the advice given in all these talks and presentations is bogus? No, it doesn’t. It is good to show range in your portfolio. If you have a lot of serious action scenes, it might be smart to also add something a little lighter. There is a balance to a good portfolio. And since a lot of animation productions are comedies, it is always good to have some funny stuff in there too. But you shouldn’t treat your portfolio as a check-list.

Good work will always show and there is no way to format your portfolio so that it hides your shortcomings. And that brings us to the last one:

4. If you don’t have the skills yet, your portfolio doesn’t matter

This is a big one. As I mentioned in an earlier post, there is this popular belief that you get hired by a studio and then, once you’re there, you really learn how to be a proper storyboard artist. And that’s just not how it works. Although it is true that you will learn a lot at your first job, that doesn’t mean you’re going to get hired if you don’t have the skills.

What I see a lot is that people are working on portfolio projects when really they’re still lacking basic story skills. Boards that look flat, shots based on their (self-perceived) limitations of draftsmanship, compositions that aren’t up to par, no sense for editing . . . If you don’t have the skills, you will not get hired.

That might sound blunt, but it doesn’t have too be all bad news. Because skills can be learned. So instead of putting all your time and effort in an epic portfolio sequence, maybe do some film studies instead. Or gesture sketches. Or just a very basic dialogue between two characters. I don’t want to sound pedantic, but you have to know how to walk before you can learn how to run. But the silver lining is that, as your skills develop, some of these training projects might actually be a valuable addition to your portfolio!

And that brings me back to what I was saying earlier: Do it quick, have fun, don’t overthink it. I believe that your best work will probably be stuff you did without being too concerned about what it would get you. I’m not saying you shouldn’t make a portfolio but I believe you should fill it with the things you love to do, not with things you think other people want to see.